Guest Blog by Geri Walton

|

| Geri Walton |

Beating the French: HMS Nympheversus Cléopâtre

In 1793, during the French Revolutionary Wars, one of the most celebrated naval encounters that occurred was between a British frigate (HMS Nymphe) and the French frigate (Cléopâtre). It all began a month earlier, when the Cléopâtreand another frigate called the Sémillante, were successfully raiding British shipping merchants in the English Channel and Eastern Atlantic. To stop the raids, the British ordered the HMS Nymphe, and the 36-gun HMS Venus into action.

|

| Edward Pellew (1757-1833) Consummate naval commander (Courtesy of Wikipedia) |

On June 17, the 32-gun Nymphe was cruising off the Devon Coast at daybreak. It was captained

by Edward Pellew and was carrying 240 men, with at least half of the crew inexperienced. It seems that because the press gangs had swept Portsmouth clean of seaman, Pellew's crew consisted of 32 marines, 80 Cornish tin-miners, and the remainder of the men were acquired from merchant vessels Pellew was escorting. It was while commanding this less than stellar crew that Pellew noticed a strange sail in the distance and decided to investigate.

by Edward Pellew and was carrying 240 men, with at least half of the crew inexperienced. It seems that because the press gangs had swept Portsmouth clean of seaman, Pellew's crew consisted of 32 marines, 80 Cornish tin-miners, and the remainder of the men were acquired from merchant vessels Pellew was escorting. It was while commanding this less than stellar crew that Pellew noticed a strange sail in the distance and decided to investigate.

Pellew quickly discovered the strange sail was the French frigate Cléopâtre. It was a 32-gun frigate, designed by Jacques-Noël Sané with a coppered hull, and it was carrying 320 men. As it was one of the French frigates that had been conducting raids against the British, Pellew gave chase. Initially, the Cléopâtre, which was captained by Lieutenant de Vaisseau Jean Mullon, fled, but realizing the Nymphe possessed the advantage and was bound to overtake them, Mullon turned the Cléopâtre and headed towards the Nymphe.

At a little before six the two frigates passed each other within hail, and as they did both crews cheered loudly. It was heady experience for the British and French crews as each side was filled with the hope of victory. The French Captain Mullon waved his hat and exclaimed, "Vive la Nation!"He then turned and addressed his crew, holding the red cap of liberty, which he waved before them. At the end of his speech, the crew "renewed their cheers and the cap was given to a sailor, who ran it up the main rigging and screwed it on the mast head."

Pellew observed this and as he was holding his own hat in his hand, he raised it to his head, which was a "preconcerted signal for the Nymphe's artillery to open." Thus, at 6:15 "a furious action commenced."The Nympheopened fire with a broadside shot against the starboard quarter of the Cléopâtre, and then the ships were "yard-arm and yard-arm; the sails and rigging being completely intermixed." This resulted in the men in the tops assailing one another because of their closeness.

Despite the two vessels being closely matched, it quickly became evident that the French frigate was taking the worst of it. Soon after the "Cléopâtre's mizen-mast was shot away; and in a quarter of an hour afterwards her wheel." This made her ungovernable and "in consequences of this double disaster she fell on board her opponent."Part of the Nymphe's crew then rushed onto the "Cléopâtre's forecastle, and another party...board[ed] through the main deck ports…fighting their way along the gangways to the quarter-deck." It took ten minutes before the Cléopâtre's colors were struck.

The duration of the battle was a short fifty-five minutes, and even though the British Nymphe may have won, it was damaged. The Nymph's"fore and main-mast were much damaged and her main and mizen stays shot away; as was the greater part of her sails, shrouds, and running rigging."As for the Cléopâtre, besides losing her mizzen-mast and wheel, she also suffered damage to her sails, rigging, and hull. Each side also lost men: The killed and wounded on board the Cléopâtre was sixty-three compared to fifty on the Nymphe.

|

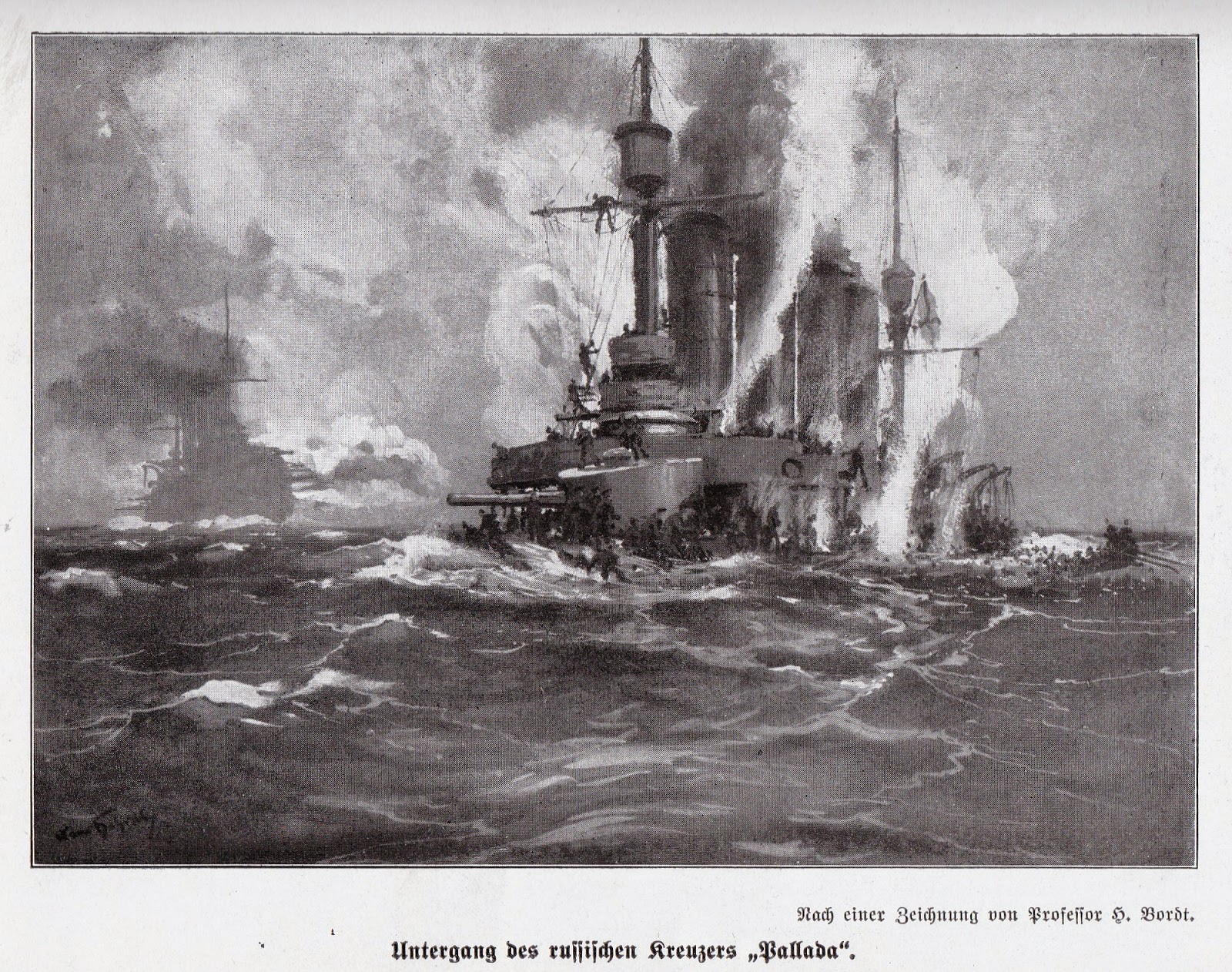

| Drawing of the action by Nicholas Pocock (1740 - 1821) Though a preliminary sketch for a later work, this conveys the excitement of the action superbly(Courtesy of Wikipedia) |

|

| Israel Pellew (1758-1832) in later life(Courtesy of Wikipedia) |

As for Mullon, he was mortally wounded during the engagement and cut nearly "in two by a round shot. During his short death agony he recollected that he had in his pocket the list of coast signals in use in the French navy, and not wishing it to fall into the hands of the enemy, he took out what he considered to be the paper; but by mistake he had laid his hands on his commission and died in the act of biting it to pieces." Thus, as the Pellew brothers were being lauded, Mullon was laid to rest on English soil in the Portsmouth churchyard. The following inscription was written on his coffin:

CITOYEN MULLON

Slain in battle with La Nymphe,

18th June, 1793,

Aged 42 years.

As to the Cléopâtre she went on to serve in the Royal Navy, commissioned as the HMS Oiseau in September 1793. In June 1794, she seized fourteen French ships from a twenty-five vessel convoy. She also served in the Indian Ocean and captured three French frigates in January 1800 off the Atlantic coast in north-western Spain. She began to serve as a prison hulk at Portsmouth in June 1806, and, in 1812, she was lent to the Transport Board and fell under the command of John Bayby Harrison in 1814. After being put in ordinary in 1815, she was sold to a Mr. Rundle in 1816 for £1500, and he broke her up after buying her on September 18.

References:

"Capture of a French Frigate," in Kent Gazette, 25 June 1793

"Naval History of Great Britain," in Lancaster Gazette, 2 February 1822

"Romance of the Sea," in Dundee Courier, 5 October 1877

Winfield, Rif, British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817, 2008

"Naval History of Great Britain," in Lancaster Gazette, 2 February 1822

"Romance of the Sea," in Dundee Courier, 5 October 1877

Winfield, Rif, British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817, 2008

About Geri Walton:

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to get a degree in History and resulted in her website, http://www.geriwalton.com/, which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s.

Her first book, Marie Antoinette’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, was published last month. It looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe, her closest confidante.Click here for more information.

You can find Geri on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/geri.walton), Twitter (@18thCand19thC), Google Plus (https://plus.google.com/u/0/117631667933120811735/posts/p/pub), Instagram (@18thcand19thc), and Pinterest (https://www.pinterest.com/geriwalton9/).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)